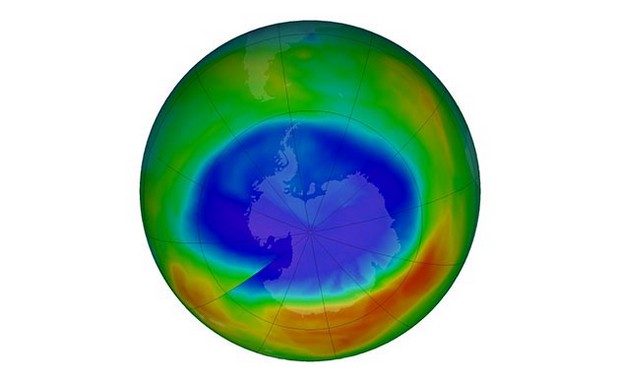

First direct proof of ozone hole recovery

Scientists claim to have been able to show for the first time that ozone depletion is declining through direct observations of the ozone hole by a satellite instrument.

Measurements from NASA’s Aura satellite are said to show that the decline in chlorine, resulting from the ban on CFCs, has resulted in about 20% less ozone depletion during the Antarctic winter than there was in 2005 – the first year that measurements of chlorine and ozone during the Antarctic winter were made.

Past studies have used statistical analyses of changes in the ozone hole’s size to argue that ozone depletion is decreasing. This study is the first to use measurements of the chemical composition inside the ozone hole to confirm that not only is ozone depletion decreasing, but that the decrease is caused by the decline in CFCs.

“We see very clearly that chlorine from CFCs is going down in the ozone hole, and that less ozone depletion is occurring because of it,” said Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre and lead author of the study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

To determine how ozone and other chemicals have changed year to year, scientists used data from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) aboard the Aura satellite. This instrument has been making measurements continuously around the globe since mid-2004. While many satellite instruments require sunlight to measure atmospheric trace gases, MLS measures microwave emissions and, as a result, can measure trace gases over Antarctica during the key time of year – the dark southern winter, when the stratospheric weather is quiet and temperatures are low and stable.

The change in ozone levels above Antarctica from the beginning to the end of southern winter – early July to mid-September – was computed daily from MLS measurements every year from 2005 to 2016. “During this period, Antarctic temperatures are always very low, so the rate of ozone destruction depends mostly on how much chlorine there is,” Strahan said. “This is when we want to measure ozone loss.”

They found that ozone loss is decreasing, but they needed to know whether a decrease in CFCs was responsible. When ozone destruction is ongoing, chlorine is found in many molecular forms, most of which are not measured. But after chlorine has destroyed nearly all the available ozone, it reacts instead with methane to form hydrochloric acid, a gas measured by MLS. “By around mid-October, all the chlorine compounds are conveniently converted into one gas, so by measuring hydrochloric acid we have a good measurement of the total chlorine,” Strahan said.

Nitrous oxide is a long-lived gas that behaves just like CFCs in much of the stratosphere. The CFCs are declining at the surface but nitrous oxide is not. If CFCs in the stratosphere are decreasing, then over time, less chlorine should be measured for a given value of nitrous oxide. By comparing MLS measurements of hydrochloric acid and nitrous oxide each year, they determined that the total chlorine levels were declining on average by about 0.8% annually.

The 20% decrease in ozone depletion during the winter months from 2005 to 2016 as determined from MLS ozone measurements was expected. “This is very close to what our model predicts we should see for this amount of chlorine decline,” Strahan said. “This gives us confidence that the decrease in ozone depletion through mid-September shown by MLS data is due to declining levels of chlorine coming from CFCs. But we’re not yet seeing a clear decrease in the size of the ozone hole because that’s controlled mainly by temperature after mid-September, which varies a lot from year to year.”

Scientists expect the Antarctic ozone hole to continue to recover gradually as CFCs leave the atmosphere, but maintain that complete recovery will take decades. “CFCs have lifetimes from 50 to 100 years, so they linger in the atmosphere for a very long time,” said Anne Douglass, a fellow atmospheric scientist at Goddard and the study”s co-author. “As far as the ozone hole being gone, we’re looking at 2060 or 2080. And even then there might still be a small hole.”