Passive cooling idea uses three technologies

An innovative system developed at MIT, which combines thermal insulation with evaporative and radiative cooling technologies, could reduce the load of air conditioners in buildings.

With no need for power and only a small need for water, the system could provide up to about 9.3°C of cooling below ambient.

While more research is needed in order to bring down the cost of one key component of the system, the researchers say that eventually such a system could play a significant role in meeting the cooling needs of many parts of the world where a lack of electricity or water limits the use of conventional cooling systems.

The system combines previous standalone cooling designs that each provide limited amounts of cooling power, in order to produce significantly more cooling overall — enough to help reduce food losses from spoilage in parts of the world that are already suffering from limited food supplies.

In places that have existing air conditioning systems in buildings, the new system could be used to significantly reduce the load on these systems by sending cool water to the hottest part of the system, the condenser. “By lowering the condenser temperature, you can effectively increase the air conditioner efficiency, so that way you can potentially save energy,” said Zhengmao Lu, a member of the research team.

The system consists of three layers of material, which together provide cooling as water and heat pass through the device. The development team says that, in practice, the device could resemble a conventional solar panel and could act as the roof of a food storage container. Or, it could be used to send chilled water through pipes to cool parts of an existing air conditioning system and improve its efficiency.

The only maintenance required is adding water for the evaporation, but the researchers insist that consumption is so low that this need only be done about once every four days in the hottest, driest areas, and only once a month in wetter areas.

The top layer is an aerogel, a material consisting mostly of air enclosed in the cavities of a sponge-like structure made of polyethylene. The material is highly insulating but freely allows both water vapour and infrared radiation to pass through. The evaporation of water (rising up from the layer below) provides some of the cooling power, while the infrared radiation, taking advantage of the extreme transparency of Earth’s atmosphere at those wavelengths, radiates some of the heat straight up through the air and into space.

Below the aerogel is a layer of hydrogel — another sponge-like material, but one whose pore spaces are filled with water rather than air. It’s described as being similar to material currently used commercially for products such as cooling pads or wound dressings. This provides the water source for evaporative cooling, as water vapour forms at its surface and the vapour passes up right through the aerogel layer and out to the environment.

Below that, a mirror-like layer reflects any incoming sunlight that has reached it, sending it back up through the device rather than letting it heat up the materials and thus reducing their thermal load. And the top layer of aerogel, being a good insulator, is also highly solar-reflecting, limiting the amount of solar heating of the device, even under strong direct sunlight.

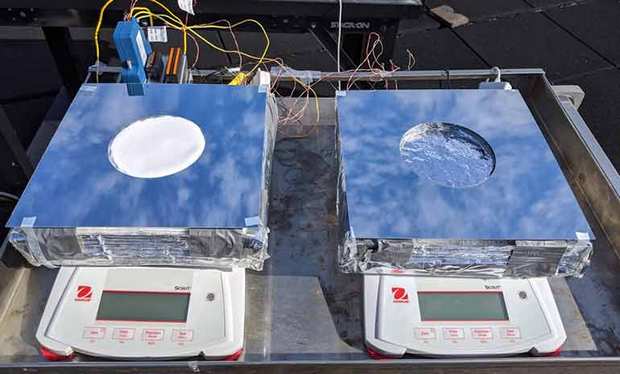

“The novelty here is really just bringing together the radiative cooling feature, the evaporative cooling feature, and also the thermal insulation feature all together in one architecture,” Lu explains. The system was tested, using a small version, just 100mm across, on the roof of a building at MIT. According to Zhengmao Lu, it achieved its effectiveness even during suboptimal weather conditions, achieving 9.3ºC of cooling.

“The challenge previously was that evaporative materials often do not deal with solar absorption well,” Lu said. “With these other materials, usually when they’re under the sun, they get heated, so they are unable to get to high cooling power at the ambient temperature.”

The expense is in the aerogel material which is key to the system’s overall efficiency. That material is currently expensive to produce, but the research team is exploring ways to reduce its cost or finding alternative materials that can provide the same insulating function. As a result, the team are loath to predict how long it might take before the system might be practical for widespread use.